Chapter 5 Coffs Storm to

New Caledonia2018

Introduction

While cruising, particularly around the world,

one studies weather systems and becomes quite

knowledgeable about their movement and

intensity.

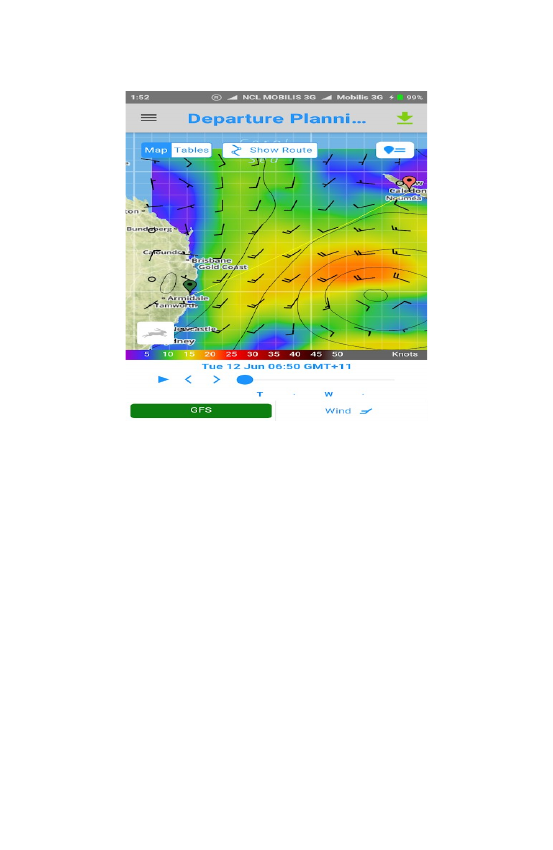

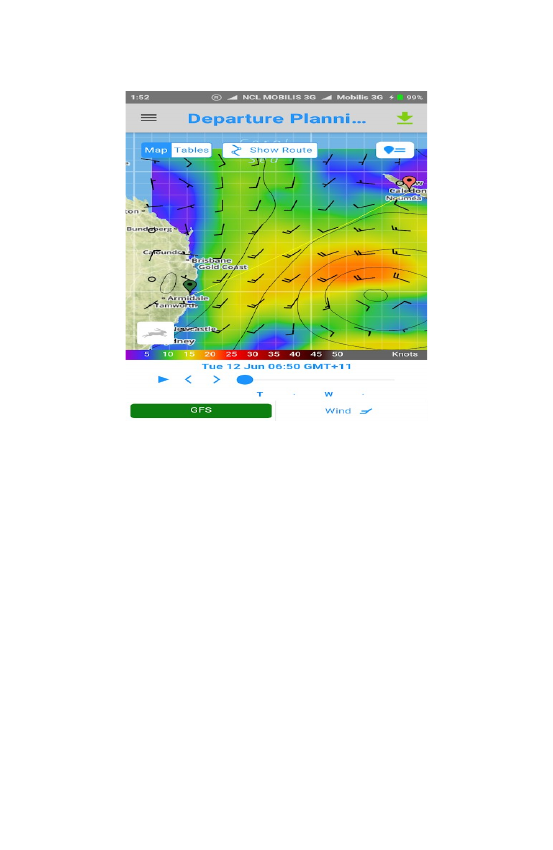

On Australia's east coast, the systems are highs

that develop over the centre of the continent

and move east, or lows that spin off the

Southern Ocean and move north up the coast

before heading eastwards towards New Zealand.

These lows can dissipate as they move or, in

some cases, deepen and become East Coast

Lows with intense weather systems around

them. They're dangerous because of the

gradient of the isobars (i.e., the closer they are

together, the stronger the wind), and the lower

the pressure at the centre, the stronger the

wind towards that centre.

Another factor is wind direction. On the west

side of the low (for those in the Northern

Hemisphere, our lows turn clockwise), the wind

blows westward and then towards the north. We

1

all know (from the 2003 film, "Finding Nemo")

about the large and strong East Australian

Current that originates in the Coral Sea as warm

water, hits the coast at 15 degrees S, then flows

south with its fastest speed up to 5 knots and

strongest point off Cape Byron, NSW, before

widening out near Tasmania.

When the southward-flowing current meets an

East Coast Low moving north, with wind

compressed between the centre low and the

coast at speeds from 10 to 50 knots, the open

sea can get ugly. The wind-driven swell and

resultant waves collide with the warm water

flowing south and the two forces of nature

collide. The waves become steep, their tops

tumbling down into the troughs. The backs of

the waves are also steep, and many a Hobart-

destined yacht has bashed through them to find

their boat and gear weren't up to this

rollercoaster ride.

A yacht of Malua's size must be very careful

when running before these winds in steep seas.

Go too fast, and you may speed down the face

into the swell ahead and bury your boat in

water. Loose your direction, and you may turn

side-on to the swell and waves. Alternatively, if

you travel slower than the swell, you may be

2

overcome by breaking waves and swamped by a

big one.

My strategy is to run before the wind at an

angle that keeps me moving diagonally to the

waves at a speed that I and the autopilot can

control.

When I set off from Coffs Harbour to cross the

Tasman to New Caledonia – a 7-day passage – I

had assumed the low would continue its track

towards New Zealand, and I would get

favourable winds all the way to my destination.

The low stalled and didn't move for days, and I

sailed right into the edge of the East Coast Low.

Here's what happened.

3

The Storm

Should I go today or check in after clearing

customs at Coffs Harbour? That was the

question I now faced. I had been watching the

low off the coast for a few days, and it looked as

if the low was moving as expected towards NZ,

so I decided to go. As I nosed out of the

protection of the harbour, I realised that what

looked like smooth water was not.

Now the wind was blowing from the south and

the current was running southwards – in the

opposite direction, so the ocean swell started to

get steeper and steeper while the wave tops

4

were being blown off. I had put in one reef

early, so when the wind reached 25 knots, the

second reef went in, only for a very short time

before I had to put the third reef in. I furled the

genoa to almost nothing, but it was out on the

spinnaker pole because I was now running

diagonally down the face of the waves – the

most prudent course in steep swells.

The wind instruments stopped working at 54

knots, but all was well on board.

Suddenly, the bilge alarm went off as I was at

the wheel guiding Malua down the waves, not

trusting the new autopilot. Once, then a second

time the shriek of the alarm sounded, and then

continuously with a scream that would wake the

5

dead. What was going on? Was there a hole in

Malua, maybe a thru-hull had come adrift?

Down below, I lifted the bilge hatch to taste the

water, but there was no need – the flow of water

from the stern area was more than a breached

tank would supply.

This was serious.

Maybe the shaft gland had come loose? I

opened the door into the engine compartment.

The shaft was OK, but the water flowing from

the rudder area was a stream. Oh no! Not the

rudder.

With the torch in my mouth, I climbed into the

engine room to look for the source, and there it

was running like Victoria Falls from the port

lazarette base – cascades of salt water – right

over the old autopilot. What? Why that much

water? Back outside, I looked at the water

flowing over the deck and lazarette, but that

couldn't cause that amount of water to enter the

vessel, so what was it? As soon as I opened the

lazarette hatch, I understood the situation. The

compartment was almost full of water with

containers floating on the surface. I removed a

few, and there, right in front of me, as one of

the larger waves broke and tumbled down

6

towards the stern of Malua, the white water

came over the swim platform and washed

halfway up the stern before draining away. Why

into the locker? The locker contained the two

gas bottles. A safety hole permits excess gas to

drain out onto the swim platform on the stern.

The gas drain hole is more than 20cm round, so

a wave that floods the swim platform can flow

inwards to the locker. Now under normal

circumstances, the odd wave over the stern

causes no harm or flooding of the gas locker, but

with the steep swell and the rolling waves from

their tops down the face and into Malua, well,

that was a different matter.

After repeated waves over the stern, the rate of

in-flow was greater than the out-flow from the

exit hole, and the locker started to fill. Its only

exit was down a gap in the floor created when I

removed the autopilot to fix it. I hadn't had the

opportunity to fibreglass the interior, and the

seawater drained into the interior of Malua,

setting off the bilge alarm.

I went down below to the emergency stores for

a wooden plug and hammer and back to face the

oncoming waves. I hung over the stern to put in

the wooden plug. A good tap/strike with the

7

hammer, and it would stay in place till I reached

land. After a few minutes, the bilge alarm

stopped, and all stations returned to normal

storm tactics.

At that point, I took a deep breath and went

below, put the kettle on for some hot tea, and

settled into my captain's chair as I watched the

wind go up and down to a high of 40 knots and

an average of just a little over 30 knots. Malua,

as always, handled the conditions well; the new

autopilot had a few bad calls, but what can you

expect, being so inexperienced?

It was now dark, but I could still see the white

waves behind me as we raced forward down

some of the steepest seas I have ever seen. Not

8

for a moment did I consider further reducing sail

or changing course... we were in a groove.

The day dawned with no sleep but an uneventful

night and many miles under the keel. I had

noticed that the wind was dropping, but then

again, it may have been that it was daylight, and

that made the conditions look a bit better. After

a few more hours of steadily declining seas and

wind, we were back on track for a smooth

passage to New Caledonia.

I have been in a few storms in my time, from a

very bad one off Cape Point in Cape Town to the

knockdown a few days out from Tonga and one

on passage to New Zealand, but this was the

most severe with the steepest waves, though

not the strongest winds. Thankfully, it lasted

just over 12 hours, which is quite bearable

considering.

9

The balance of the trip was very easy, with the

sun coming out and the wind dropping on some

occasions, which required I start the engine. I

was able to time my arrival for dawn to go

through the pass and motor towards Noumea

city and marina. I made the mistake of telling

the marina I was not going to stay with them, so

I was relegated to the back of the line for

clearance and, in fact, had to be boarded by Bio-

security at the public wharf in the SW - not

convenient. I did stop for fuel at the end of the

jetty and some bread, then off to the Orphelinat

Bay anchorage to get the tender ready to do the

10

rounds to clear in. A simple process requiring a

few km on my folding bike.

Restock and ready for Denny to fly in for a few

weeks cruising these delightful islands.

COVID interrupted my cruising plans and Malua

did not get the attention all yachts deserve

during that period. However when all was

shipshape and it got cold in the winter I sailed

north to warmer weather. The trip home had

some surprises in store.

11