Chapter 3 Pacific Storm 2014

Introduction

Crossing the Pacific on the way home after five

years in the Mediterranean and two years in the

Caribbean and USA, I was expecting an easy

run.

I had a flat sea almost all the way from Cape

Hatteras to Cuba and then an easy passage

through the Panama Canal and on to the

Galápagos. The time there was enjoyable, with

some land travel. The 19-day sail from the

Galápagos to the Marquesas Islands, with winds

between 12 to 18 knots, was every single-

handed sailor's dream cruise. Warm, moderate

winds always behind the beam.

French Polynesia is the world's best cruising

ground, with protected atolls, clear water, and

wonderful drift dives through the channels.

Eventually, I had to leave this paradise from

Bora Bora and head on to Tonga to reach home.

Not only did I leave in a rush due to

bureaucratic pressures, but I also left knowing I

was heading into unsettled weather as I moved

from the calm areas around the equator towards

1

the tropical latitudes and the Southern Ocean

further south.

What happened on this leg wasn't in the plan, and

the impact and consequences have had lasting

maintenance repercussions that I didn't uncover at

the time. Here's the story of this storm.

The Storm

Malua left French Polynesia after some difficulty

with my crew member who did not want to leave

Bora Bora. I left her in the hands of the local

Gendarme and set sail out into a very unsettled

weather system. I had no option but to leave,

so off I went. After two days, the main engine

started to give problems. It was either water in

the fuel or the fuel was contaminated. The end

result was I could run the engine to charge the

batteries but not move the boat forward. Not a

big deal in a sailing boat; however, there was no

wind, so I just sat and waited.

2

Be careful what you wish for.

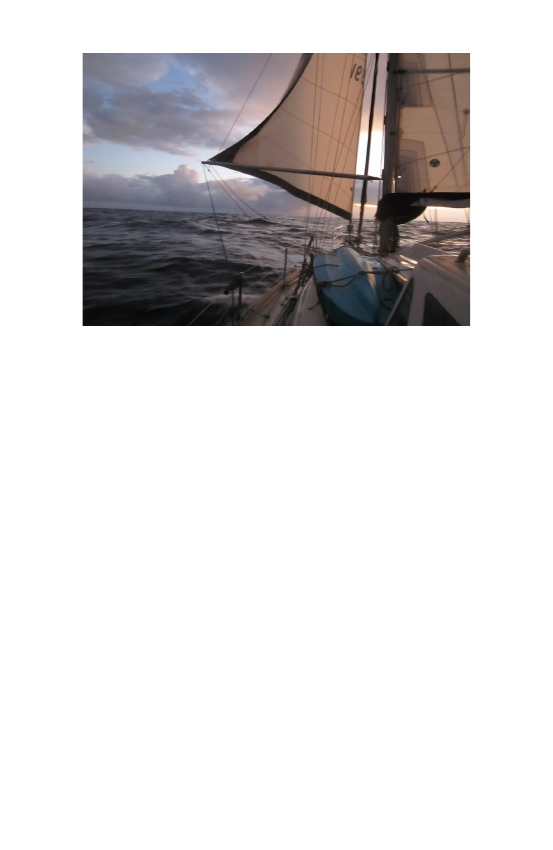

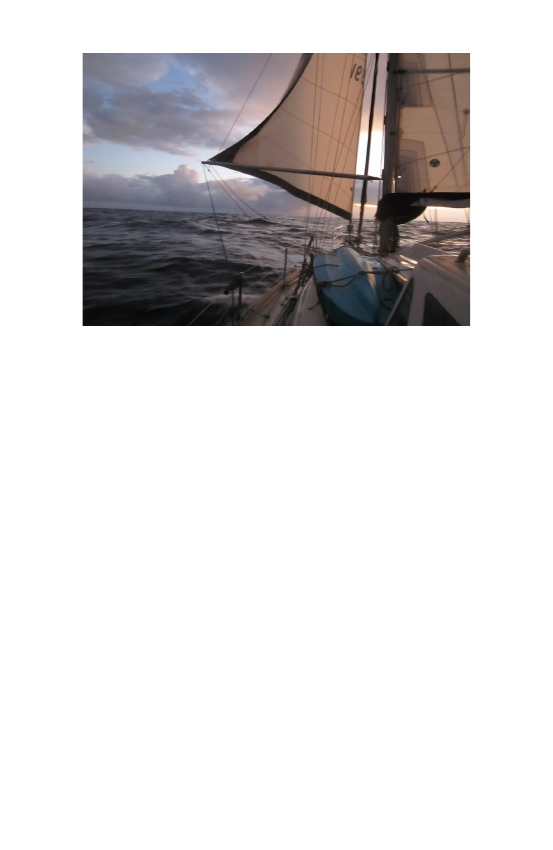

On the third day out, at dusk, the wind started

to rise. By midnight, I watched as the wind rose

from right astern, first 20 knots - OK, put in one

reef; then 25 - OK, put in the second reef and

furl the genoa; then 35 - well, it can't go much

higher. The boat was now doing 8 to 10 knots

downwind.

3

This is where single-hander lethargy sets in.

You do nothing either because you're tired or

you think it will get better. When the wind was

at 40 knots, I decided to take the third reef in

but did not move from my captain's chair. It

was then the wind rose to 45 and then 47 knots

and BANG - the sail tore between the second

and third reef points. Now there was no option

but to take the torn sail down.

I stepped up into the cockpit and started to

move forward when a large wave washed all

over the port side of the boat. Time to clip onto

the lifelines, turn all the outside lights on, and

4

secure the sail. Not a difficult job because Malua

was still running before the wind and waves.

The autopilot was handling the situation well.

When the sail was secure, I only had a small

furled staysail out, and Malua was still doing 5 to

6 knots along the rhumb line to Tonga - 6 days

away.

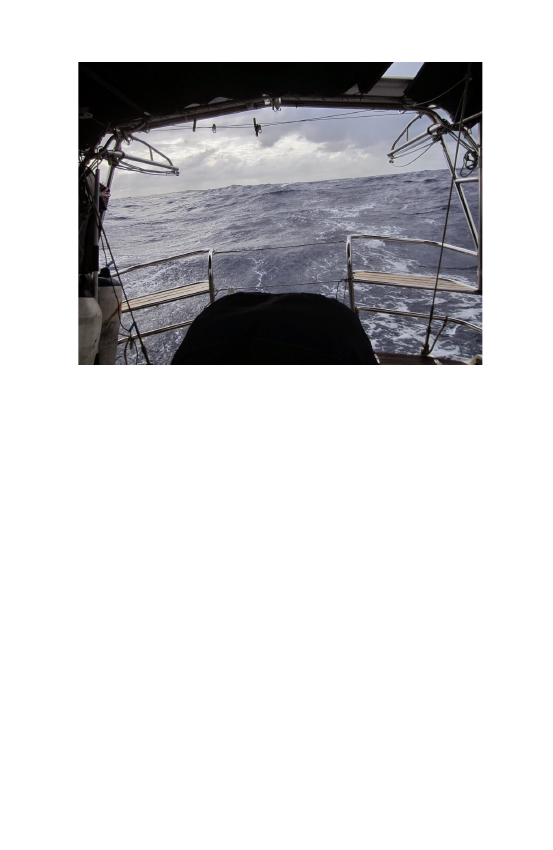

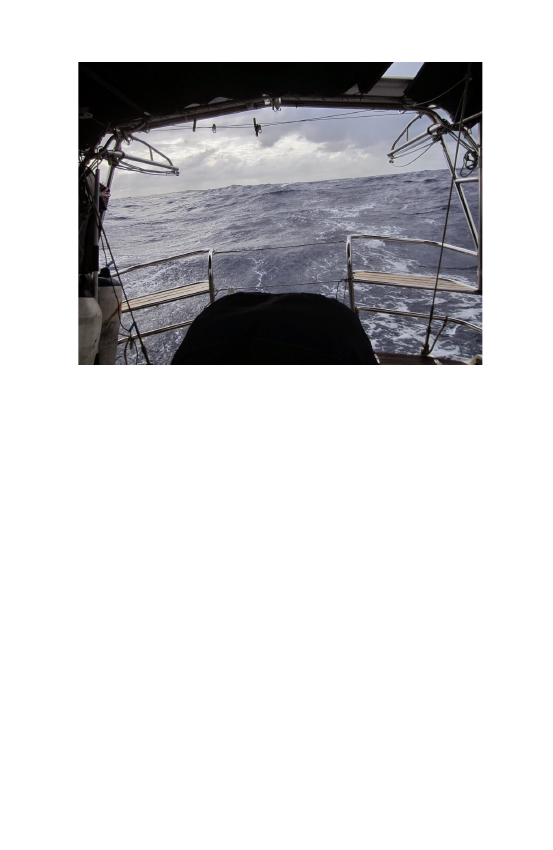

I slept well the rest of the night, but by morning,

the seas from east of New Zealand had built to a

massive 5 to 6 meters. Thankfully, they were

quite ordered and pushing me in the right

direction.

That afternoon, while I was in the captain's chair

at the nav station, the boat was slammed over

to the starboard side by a huge wave. The

dorade vent over the stove started to flood

water, and I found myself on my side

underneath a waterfall of seawater coming

through the closed companionway hatch. Before

I realised what had happened, Malua had righted

herself, and I was drenched through.

There was water everywhere with about 2 inches

over the floor.

I set about getting rid of the water by sweeping

it into the bilge. Days later, I was to find the

batteries swimming in a sea of water in their

5

purpose-built battery compartment. I would find

water everywhere in the aft section of Malua.

My quarter berth was wet, as were things on the

chart table. The final water damage would be

revealed days later.

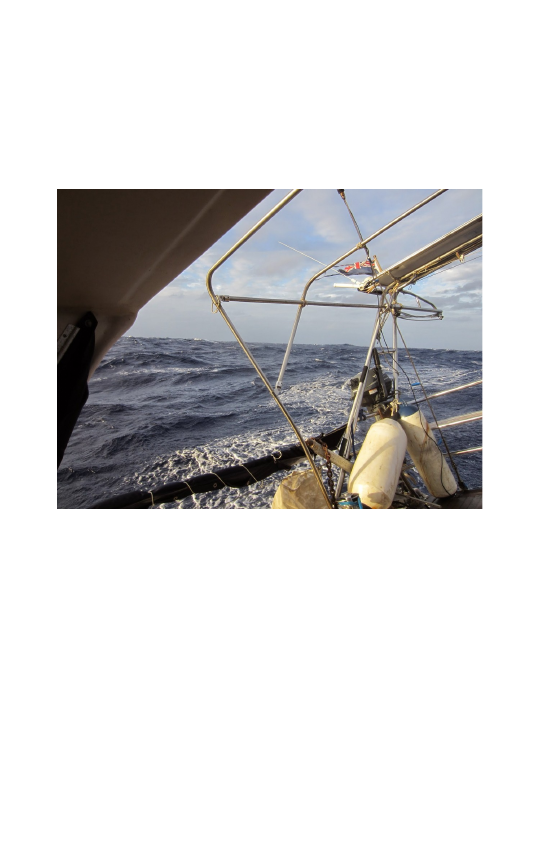

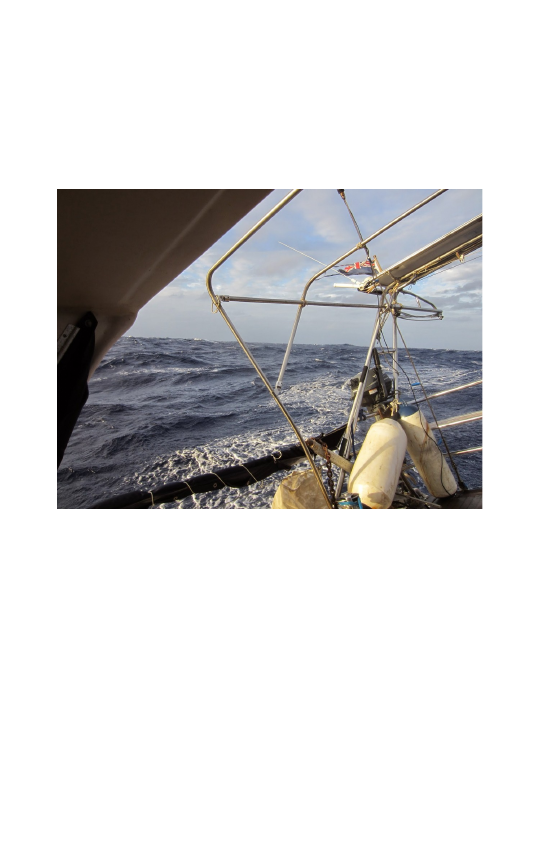

I then realised that there was something

flapping in the cockpit. I opened the

companionway and looked out to find all the

canvas from the bimini and weather cloths

ripped to pieces. The two fenders secured at the

stern had gone. The stern anchor tied to the

lifeline was over the side, attached to the boat at

the end of the anchor chain. The life recovery

ring was trailing astern on its line. All the sheets

6

and lines kept in the cockpit and under the hard

dodger were somewhere else. It was a mess.

Luckily it was light, so I set about retrieving the

things trailing overboard and securing the other

lines in their correct place.

I was to find out later that the engine fan vent

located in the cockpit had been flooded along

with the large cockpit locker containing one

outboard engine. The other on the rail had had

a good seawater submersion.

What could I do? Just run before the wind with

only the small furled staysail to give me

direction and drive. Five days later, I was off the

northern tip of Tonga, hoping for a tow into the

harbour by one of my friends. I contacted them

on the HF radio, but they could not or would not

give me a tow into the narrow entrance to the

port of Neiafu on the northernmost island of

Tonga. You soon find out who your friends really

are.

7

I organised a commercial tow into the harbour,

cleared in, and took a mooring buoy in Neiafu

harbour. I had been here before in 2004.

Relieved that I had made it to a place where I

could get the engine fixed and repair the sail.

The next chapter occurred a few years later.

No magical moment on Malua here.

8