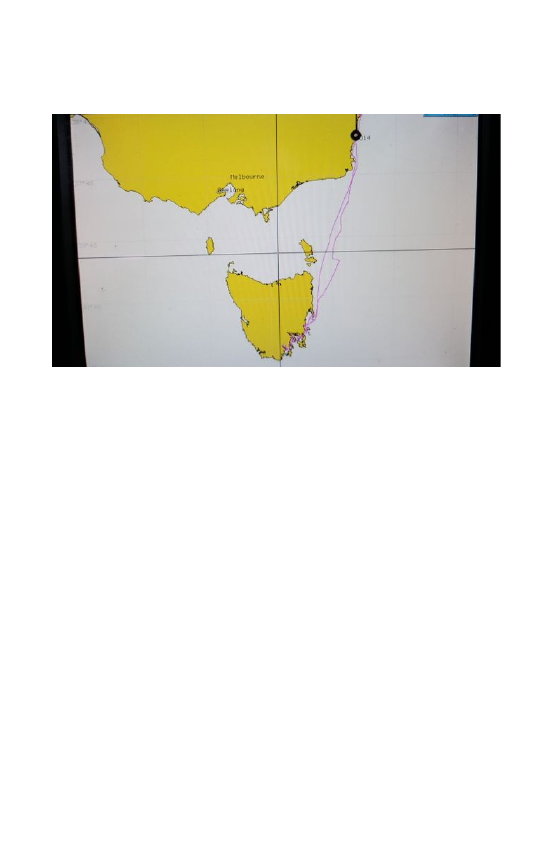

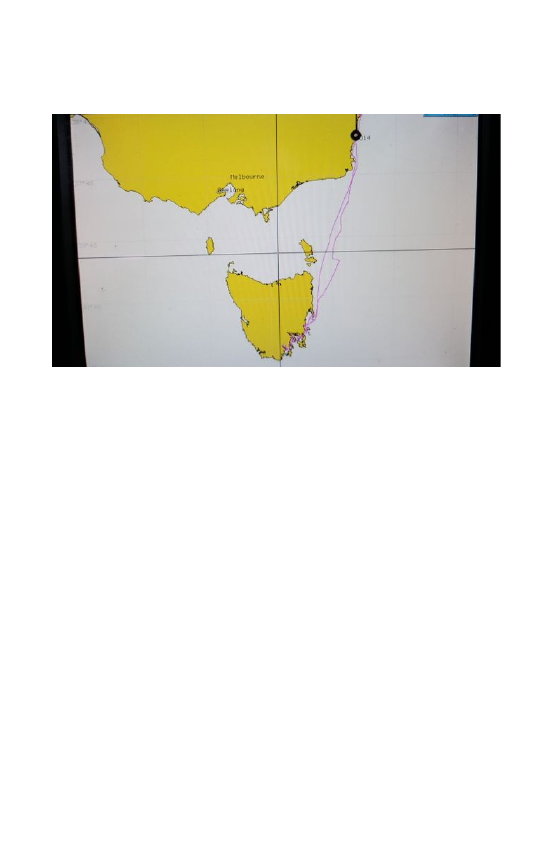

Chapter 4 Bass Strait 2017

Introduction

This event came out of the blue on what should have

been a routine sail south to Tasmania. As many

crews on the annual Sydney to Hobart yacht race

know, crossing Bass Strait is no walk in the park if

the sea turns nasty. I had the Bureau of

Meteorology (BOM) forecast and also took advice

from another prediction system – my mistake.

Here's my story of being hit by an unexpected cold

front coming north from the Southern Ocean and

meeting the easterly flowing waters of Bass Strait.

The Storm

I know not to leave port on a bad forecast, and

being in Bermagui meant I was safe and sound

until the forecast looked good. Now the lesson

to learn is which forecast to rely on. I usually

check two or three. The BOM model and the

USA model are the ones I consult. On this

occasion, I followed the BOM model but relied on

the Predictwind app on my phone. It showed

three days of northerly wind then a swing to the

west. All good. The westerly would come off

1

the land and make the sail down the Tassie coast

nice and flat.

I left Bermagui at noon and set sail for Bass

Strait down the coast southwards. The vessel C-

Star left soon after me. The wind was from

behind and the current was with me, so I made

good time down the coast. I passed Eden late

that afternoon and set off across the strait. I

had my first meal on passage and settled down

for the night, knowing there might be ships. It

was a quiet night with no real traffic. The

following morning, I tried to call C-Star on VHF

as arranged but only got a short, disjointed

message. I heard Painsville calling C-Star on

VHF, so I spoke with them on HF and said they

were behind me and not lost, as a result of

Marine Rescue initiated search. They had not

2

checked in with Lakes Entrance, miles out of

their VHF range.

At that stage, I had done just over 160 nm in 24

hours, a good run. The wind was over 25 knots

and increasing, so I put in the second reef.

Then it hit - a front from the South. Totally

unexpected and with winds more than 40 knots.

I dropped the main and furled the genoa. I

raised the main with the 3rd reef in and started

to beat into the wind as the sun set, but the

wind continued to increase. My log notes

indicated it reached 45 knots at 4:00 am. Not a

great start and so unexpected, but Malua was

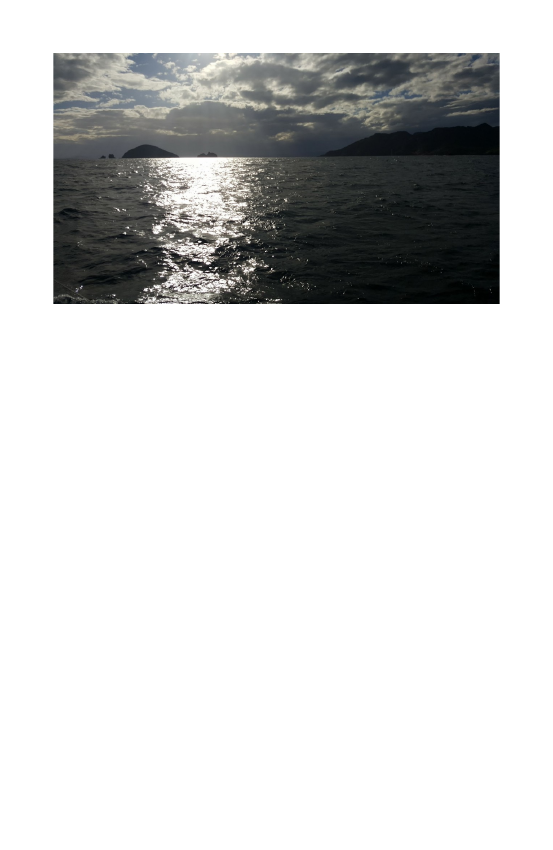

going well into a rather calm sea. Then as I

watched, looking forward with my spreader

lights and my forward-facing spotlight

3

illuminating the deck and sea, the wind rose in a

series of gusts well over 45 knots.

The waves were now building and Malua was

moving forward nicely. Malua started to rise

over a wave and then it hit. A big one over the

starboard bow. White water filled the staysail

and bang - the stay parted at the head, and I

watched, as they say, in slow motion, as the sail

and furler went over the port side into the water.

Spring into action. Let go the main halyard and

drop the sail, but it jammed before totally

furling. It stuck flapping in the now 45-knot

wind. I finally pulled it down and moved forward

to try and get the staysail on board. It was at

this time attached at its head to the halyard up

the mast and the base was

secure. The sheet was

holding it onboard, but a lot of

the sail and rigging was in the

water. Then the base with the

furler drum came loose and

went over the side.

I was able to secure a line to

it and, via a block and the

winch, pull it over the lifelines

and up to the bow anchor

4

area. It was secured, but the head was over the

port side supported by the halyard. If I let that

go, it was dangerous, so I passed a line around

the sail and pulled it alongside the boat but up in

the air just above the furiously spinning wind

generator. Stop, think. OK, stop the wind

generator by using the electric brake and tie off

the blades. I completed that in a few precarious

minutes and set about recovering the head of

the foresail. I slowly loosened the halyard and

lowered the bent and twisted Profurl furler

alongside the boat. All this time I was wallowing

in the ever-increasing waves and wind. Finally,

the sail and furler were secure along the port

side of Malua, and I could now focus on sailing

the boat with the sails I had left.

I looked at the wind gauge and found the wind

was still in the 45 or more range. I was not

going anywhere this evening. I unfurled a bit of

the genoa, pulled hard on the sheets, and

turned the wheel into the wind and tied it off.

Malua was now heaved to or lying a-hull. It

doesn't matter what you call it, but Malua was

sitting nicely in the water. There were very few

large waves and none like the Tonga storm from

the Southern Ocean. I took a shower, changed

5

into some dry clothes, and settled down to wait

for dawn.

I was 50 nm from Flinders Island and moving in

a south-eastern direction at about 2 knots with

very few waves disturbing me. I climbed into

bed and set the alarm for 27 minutes and slept.

When I woke, I looked out the portlight adjacent

to my bunk to check the waves, wind, and

weather – nothing had changed. The wind was

still at 35 knots or more. Back to sleep. So it

went until the sun rose. Wind still at more than

35 knots, but the warmth of the sun was a good

sign. At about noon, almost 18 hours after the

staysail came down, I started the engine and

turned south for Hobart. The sea had become

more confused, and we made only slow

progress.

Then the radio went off: "All ships, all ships, etc.

Has anyone seen C-Star?" I again

communicated with Painsville, this time on HF,

and told them about the storm last night and

that I was OK heading to Triabunna and would

try calling C-Star on VHF. No luck.

I subsequently heard they had telephoned

Marine Rescue with their sat phone to say they

were returning to Eden. This message had not

6

been passed to Canberra. I never check into

Marine Rescue for this reason. They will start a

search just because someone travelling along

the coast has not been able to update their

plans. Thankfully, Canberra knows better and

uses all available resources to contact vessels in

the area to assist.

The wind dropped as suddenly as it rose, and I

continued to motor down the coast for the rest

of that day and through the night. At 5:00 am

the following morning, I switched from the

forward diesel fuel tank to the aft tank. As I

switched, I watched the vacuum gauge go from

yellow (good) to red, and the engine started to

splutter as it could not getting any fuel through

the line. I could see a dirty black mass in the

fuel filter. A quick switch of filters to the

7

alternate and a switch of tanks back to the

forward tank, and I was off again.

Now I had a problem. No wind and little fuel in

the forward tank, and about 80 nm to any

destination. I always keep 40 litres in two

containers in the aft cockpit locker. I lifted the

first, full, so it went into the forward tank. I

located the second, but it was empty. What had

gone wrong?

The only feasible solution was to get fuel from

the aft tank, but it would not come through the

block lines. So I used the outlet at the base of

the tank to draw off fuel. I drained some fuel

into a container, but it was full of black fungus

from the diesel algae. Black sludge like jelly. I

tried again and again till finally, it started to run

reasonably clear. OK, I had clean fuel in a small

container but blocked lines. What to do next?

How could I filter it? The only thing I could think

of was through a small funnel with a coffee filter

placed in it. It was a slow process, drop by

drop. It required many refills to get the clean

fuel in the lower container. Finally, I had enough

extra fuel – about 5 litres to make it to

Triabunna if the wind did not come up.

8

Still no wind as I rounded the southern arm of

the Freycinet Park. The sun was starting to set,

and I had not reached Prosser Bay near Orford.

But no worries, there is a full moon tonight, and

I will be able to see the land which I know from

previous cruises. I motored at the optimum

speed to save fuel as it got dark. The moon was

in the east just above the mountains as I passed

northeast of Maria Island and toward the bay.

Then the moon disappeared behind the

mountains, and I was left in total darkness.

The light of Orford was my only guide along with

the chartplotter and radar. I eased into the bay

and dropped the anchor. I pulled back to see

that it was set well and turned off the engine.

Silence. Food, shower and sleep.

9

I woke after a great night's sleep to find I was

right in the middle of the bay, a long way from

the shore.

I cleaned up the mess down below and followed

another yacht up the channel of Spring Bay and

into Triabunna. I was right out of fuel as I tied

up alongside and tried to arrange a tanker to fill

Malua's tanks.

No magic moment on Malua

The next Chapter just highlights the importance

of a weather forecast.

10